Uncovering the Reasons Behind Japanese Companies' Success: A Look at Employee Value and the Kaizen (改善) Approach

- michelecatano

- Jul 10, 2024

- 13 min read

I dive into a topic that is dear to me - How Japanese studios have been approaching this rapidly evolving market and make the most of out it while many Western companies struggle

While we work on a new analysis of a recent hit, I wanted to jump into a topic that has been heavily discussed in the last months: the current state of the console/PC gaming industry in the US and the “layoff crisis” that started in 2023 and shows no signs of stopping.

I often come across articles drawing comparisons with the “Japanese approach” and why Japanese companies are not undergoing the same, heavy restructuring phase as Western ones. Many of these articles and debates mention how Japanese laws prevent companies from laying off people as easily as it happens in the US. Suggestions even hint that unionization in the US might be the solution. As a die-hard fan of the Japanese gaming landscape, and of Japan overall, and having lived there long enough, I thought I would give my two cents on the argument.

While it certainly plays a role, I think this exogenous factor (the law) is more supplementary than primary in nature. Moreover, I believe that Japanese companies would not have laid off people even if national laws were not so strict. There are much more powerful endogenous reasons as to why we are seeing this big difference in behavior.

Of course, owning a portfolio of appealing and world-renowned IPs is at the core of any gaming company's strategy operating in the HD space. On the surface, this strategy around IP management might seem the same anywhere in the world, but I argue that the way Japanese and Western companies are actualizing it is incredibly different.

Specifically, I will touch on the following four topics in this article:

Topic 1: The Value of the IP versus the Value of the People Behind the IP

Here in the Western markets, there is an underlying assumption that a strong IP’s fanbase will remain loyal, active, and passionate over time just because of the “brand attractiveness”. The people working on an IP might move around and change, but the IP will stay, and this is what the companies care about. I argue that this is not completely true and doesn’t consistently work out that way in the gaming industry. To keep an IP alive and valuable over time, the most important thing is to have the right people taking care of it and making it valuable.

I have collected data for 14 publishers/studios (Bandai Namco, Capcom, Konami, Koei Tecmo, Nintendo, Sega, Square Enix, Bethesda, Xbox Studios, EA, PlayStation Studios, Take Two, Activision Blizzard, and Ubisoft), over 50+ gaming IPs, and looked at who, over time, has been creating and shipping these games (mostly as Executive Director or Executive Producer). What I see, on average, is that there is a big gap in tenure between Japanese and Western companies in regard to when a well-known IP appoints people to those roles.

Some examples are memorable, such as Katsuhiro Harada, who has led Tekken since its inception in 1994, or Eiji Aonuma, who worked on The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time with Shigeru Miyamoto back in 1998 and has been Creative Director/Producer of all the main Zelda games up to the present. These people have been working their whole lives on the same incredible IPs and their names is directly associated to their products. Something that is really hard to find in the West.

Moreover, in Japan, when the creator of a series leaves, the role is generally taken over by people who have accumulated many years of experience on that same IP. This enables consistency and a deep understanding of the IP and the games in development, which helps guarantee that the company will hit the targets and expectations of the majority of gamers.

Such consistency is very hard to find in Western studios, where people move around much more frequently and easily. This is absolutely fair on a general level, but it leads to a lack of knowledge and understanding of the roots of the IP.

To make it more tangible, I created a template for some of the series that I have analyzed. I will present just a couple of examples in this article, but if you’re interested in the whole database, feel free to reach out. Also, all the data has been manually collected, so if you spot an error, let me know!

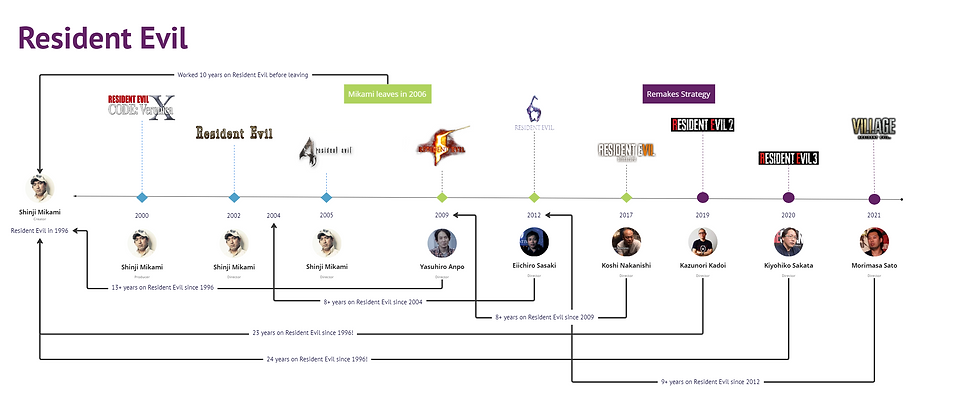

See below for some analysis on the IP management history for three series: Assassin’s Creed (AC), Resident Evil (RE), and Yakuza (sorry, Like a Dragon). The arrows under a specific person trace back to when that person started working on the series.

Assassin's Creed IP Management

A few takeaways:

The IP creator, Patrick Desilets, worked for only approximately 3 years on the IP before leaving the series.

The first two games released after Desilets’ departure were AC Revelations (2011) and AC3 (2012), both directed by people who had never worked on an AC game before - especially Hutchinson, who joined Ubisoft from EA less than two years before AC3’s release.

Doing a quick calculation, the average time working on the Assassin's Creed IP before leading a project is less than 3 years (2.8 years).

As a big fan of the first couple of games (how cool were the parallel plot lines between Altair and Desmond Miles?), the modern-day section of the game got lost somewhere between Brotherhood and AC3. Well, now I know why..

Resident Evil IP Management

Mikami (aka the Resident Evil creator, who worked on all the main episodes until RE4) left Capcom in 2006, meaning he had already worked on the IP for more than 10 years (the first RE was released in 1996).

The first RE without Mikami (RE5 in 2009) was directed by Yasuhiro Anpo, who had worked on all the previous RE games since 1996. This means that Anpo took the leading role after 14+ years of experience with the IP!

The Resident Evil remake strategy, which arguably relaunched the series to new heights, especially in the West, was led by Kazunori Kadoi (Executive Director of RE2 Remake) and Kiyohiko Sakata (Executive Director of RE3 Remake) - both of whom worked with Mikami on the first RE in 1996 and are credited in basically all the RE games along the way!

The average time needed for a person to lead a RE game is 14 years

So, while US companies struggle to keep IPs alive, Japanese companies built an incredible foundation. I am not surprised that while the value of IPs such as Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Far Cry, Halo, Deus Ex, and others is at an all-time low, the value of many Japanese IPs, including some that most of the Western audience didn’t even know about ten years ago (Yakuza, Shin Megami Tensei / Persona), are now at an all-time peak.

Yakuza / Like A Dragon IP Management

The creator of the series, Toshihiro Nagoshi, worked on Yakuza until 2016 before leaving (the first Yakuza was launched in 2005, so he worked on it for more than 11 years).

The remake strategy was led by Koji Yoshida (Yakuza Kiwami) and Hiroyuki Sakamoto (Yakuza Kiwami 2), after 7+ and 12+ years of experience on the IP, respectively.

The end of the Kiryu Saga and the revamp of the IP under the name Like a Dragon was managed without Nagoshi and led by Ryosuke Horii, who had been working on the series since 2009 (Yakuza: Like a Dragon was launched in 2020), so he also had 11+ years of experience with the IP.

Also here, the average tenure of a person at the Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio before being able to lead a main Yakuza game is 10 years

And I could replicate this exact story for numerous other Japanese IPs (Zelda, Monster Hunter, Miyazaki with Dark Souls/Elden Ring, Street Fighter, Dragon Quest, Metal Gear (until Hideo Kojima left), Shin Megami Tensei/Persona..) and Western IPs (Wolfenstein, Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Gears of War, Halo, Bioshock, Max Payne, Diablo, Far Cry..). The three examples provided are not the best- (for Japan) and the worst-in-class (for the West), but the respective average observed behavior.

Aren't Japanese IPs Just Better?

The obvious follow-up question here is: “Aren’t Japanese IPs just better?”. And the answer is no.

First of all, there are examples in the West that show how consistency can be the right approach here, too. Many people might not know, but all Grand Theft Auto (GTA) games since GTA3 have been led by Leslie Benzies, who was working at DMA Design (the studio behind the original GTA) at least since 1995 and have been written by Dan Houser (co-founder of Rockstar and solo writer for GTA London 1969 in 1997). By the way, both left Rockstar (Leslie in 2016, Dan in 2020), so we will see what the future holds for the series. Another good example is the Elder Scrolls series, mostly led by Todd Howard since 1996 (Oblivion (2006) was directed by Ashley Chang, who had worked on the series at least since 1998). So, there are (a few) examples of a similar approach in the West, and it works.

At the same time, there are examples of Japanese series that have lacked the usual consistency for one reason or another. And, of course, these IPs are struggling, too. A few examples? Castlevania and Silent Hill. When Koji Igarashi (who had worked on Castlevania since 1997) left Konami in 2014, the series was already outsourced to Mercury Steam, a third-party studio based in Spain. The two games made by that studio (Lord of the Shadow in 2010 and Lord of the Shadow 2 in 2014) didn't resonate with the audience and we have not seen a new chapter since then. And I would argue that even Final Fantasy, especially in the last couple of iterations, has lost the “Japanese” approach. Tabata, FFXV's director, had no experience with the main installments of the series, although he directed FF7 Crisis Core, and FFXVI's director Yoshida had never worked on a single-player FF game, although he probably earned his spot by saving FFXIV from disgrace). People might disagree, but also Nintendo’s Metroid series has been affected by this approach. Metroid games have been split between the East and West, with many Metroid Prime games developed by US-based Retro Studio since 2002, while the others were developed in Japan, led by Yoshio Sakamoto. Moreover, the Samus Returns sub-series was outsourced to Mercury Steam (Spain), and the upcoming Metroid Prime 4: Beyond is being led by the Retro Studio, although initial development was managed by Bandai Namco Studios.

So, no, I don't think Japanese IPs are just not better.

Is there a macroscopic effect that shows some results of the two different approaches?

To answer this question, I looked at some historical data, i.e., the yearly Top 20 chart on Metacritic from 1999 to 2024. At the end of the 90s and the beginning of the new millennium, almost half of the Metacritic Top 20 was occupied every year by Japanese games (8 in 1999 and 2000, 10 in 2001 and 2013). The 2005-2015 period was difficult for Japanese companies for various reasons (a stronger support from PlayStation to Western studios with the launch of PS3, the launch of an American console, the first Xbox in 2001, some not really successful Nintendo consoles, the GameCube in 2001, and the WiiU in 2012, among many other reasons) and the number of Japanese games in the Metacritic Top 20 went down to 5 in 2007 and 2008, touching a minimum of only 3 games in 2012. But fast forward to 2023 (and 2024) and we again have 8 games in the Top 20 (with a peak of 14 in 2019). But why do I think this is meaningful? Well, because the Japanese games that topped the chart in 1999 were Soul Calibur, Gran Turismo, Final Fantasy, Resident Evil, Donkey Kong and Mario. You still see most of these IPs around, no? The Japanese companies have resisted bad times and kept working on ther IPs anyway. And now they reap the fruit. On the other hand, the Western games that topped the chart in the same year were System Shock, Legacy of Kain, Syphon Filter, Homeworld, Tony Hawk’s, Medal of Honor, and WipeOut. No need for an explanation here - not even one of these series is still around.

I believe that this shows the resilience and the hard work that Japanese companies have put in the last 20, if not 30 years, to take care of their IPs and especially of the people behind them.

Topic 2: Continuous Improvement (改善) vs Total Disruption

A concept that I really love from Japan is 改善 (Kaizen), which is generally translated as “continuous improvement”, although the kanjis convey more the sense of “keep making changes to make something better”. I first encountered the term when reading Taiichi Ohno’s book Toyota Production System and have been fascinated with the concept ever since. The idea is to never disrupt something and aim for big changes, but instead to focus on smaller but more frequent changes, which will lead to a significant advancement in the end. This goes against the Western philosophy somewhat, and I believe it is at the foundation of some basic differences between the US and Japanese financial markets, such as the much lower rate of startups (more on this in the last point of the discussion) in the latter and the quicker pace at which companies grow and reach impressive valuations in the West.

How does this difference impact the gaming space? I believe this translates into Japanese companies almost never disrupting fundamental aspects of an IP or a studio. This is not to say that they never change, but the changes are moderate, especially on delicate aspects, such as the business model.

Both Japanese and Western companies have been fascinated by the promises of LiveOps and F2P monetization models and have made many bets in the space, but Japanese companies have avoided betting their most valuable IPs and studios and have not gone all-in. On the other hand, from Marvel’s Avengers to Suicide Squads: Kill the Justice, and from Halo Infinite to Anthem and Redfall, there are plenty of examples in the West - and I did not even mention the recent PlayStation approach, which is having incredible repercussions on their lineup since 2023 - that show the consequences of these big and bold bets.

Vice versa, Japanese companies avoid this risk in two ways:

Launching multiplayer-focused games based on new or less important IPs with the involvement of smaller studios. Arguably, many of these tentatives fail anyway, but the overall impact on the studios and publishers is much smaller (for example, Babylon’s Fall or the recent Foamstarts by Square Enix or Capcom’s Exoprimal among many others).

Introducing F2P and LiveOps features on top of a strong foundation of proven mechanics.

The first point is also supported by examples like Helldivers 2, a game with a somewhat unknown IP to the mass audience until now that was anyway able to grab the interest of a large fanbase because it is a really well done product. In a few words, you don't need an already established IP to be successful in this new space.

The second point is incredibly valuable and often dismissed by Western companies. Premium games such as Tekken 8 and Dragon Ball Xenoverse 2 are full of microtransactions (MTX) - actually, the overwhelming majority of the recent Capcom games have an incredible amount of MTX! Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth’s New Game+ mode is basically sold as a standalone $15 MTX, too. When each of these games has been launched there were some discussions online about this approach, but not much more than that. I believe the reason is that all these games propose the solid foundational aspects that have characterized their series for a long time, which keeps players happy. On the other hand, when the players who loved the single-player focused Arkham trilogy (myself included) looked at the next work of the beloved Rocksteady Studio, well, the only thing to talk about regarding the game was that it was supposed to be “a new, genre-bending action-adventure shooter that can be played solo or with up to four players in online co-op”. Exactly what any fan wanted.

In conclusion, I believe that US companies have been too hasty in dismissing the foundations of what have made some gaming IPs important over the years and jumped into the LiveOps frenzy. A more steady and rational approach would have brought fewer disasters, in my opinion.

Topic 3: IP Annualization

This is pretty straightforward, and I will keep it simple. In order to stabilize returns and make a gaming company more palatable on the financial markets, many US companies have tried to serialize IPs. While sometimes this works and makes sense given the nature of the product (Call of Duty, EA Sports FC, F1, Football Manager), for many other IPs, it has led to burnout among the playerbase, who just stopped buying the same product year after year. Honorable mentions in this case are Need For Speed, Assassin’s Creed (it’s incredible, but they reached the point of releasing two main AC games in the same year in 2014!), Far Cry, Tony Hawk’s, Guitar Hero (RIP), and potentially, the whole TellTale Games business model goes into the same category.

I haven’t seen any Japanese company even try this approach, although all of the main Japanese publishers and studios are quoted on the stock market.

Topic 4: Different Barriers for Incumbents to Change the Market

This last chapter also serves as a closure to the discussion. Although I mostly discussed endogenous reasons why we see very different behaviors between Japanese and Western gaming companies, I believe there is a big exogenous factor that is worth at least mentioning and that makes any tentative to imitate the Japanese approach fruitless in the West. And this is the general business landscape. It is true that the console/PC industry has been heavily impacted by the growth of mobile gaming, but US companies face more pressure from many other fronts compared to Japanese ones. And I am not only talking about investors and the financial markets, but mostly new incumbents.

Without the need to draw the whole Porter’s Five Forces graph, both the US and Japanese gaming markets face similar situations in terms of suppliers and buyers’ forces, rivalry from existing competitors, and threats of substitute products and services (mostly mobile gaming and other forms of entertainment, such as Netflix).

But the difference is in the last force, i.e., the threat of new entrants. In the US, this threat is very high and has already had a huge impact on the market. Incumbents such as Roblox (but also Epic Games with Fortnite to a certain point) have increased competition drastically. Fortnite and Roblox are the two most played games on PC by far in the US, and the situation is also getting pretty similar on console. (Fortnite is the most played and Roblox sits at 5 currently, but the latter was recently launched on Xbox and PlayStation so there’s time to grow). Although these games are also successful in Japan, the impact has not been the same for various reasons - from being Western-focused games and, thus, not always spot on with the preferences of the Japanese audience, to the fact that these games are, first and foremost, PC games, a platform that has been pretty much ignored in Japan up until now. Because the environment for startups and new competitors to flourish in Japan is not as favorable as in the US, Japanese companies are also less inclined to make big changes and revolutionize their approaches and tactics, which is aligned with the previous points of the discussion.

This was a lot of fun to write and I hope you enjoyed the information provided. In my opinion, one key lesson for Western studios to take from the current success of Japanese companies is to reassess the significance of the individuals they have on board in determining the value of an intellectual property.

Feel free to reach out to talk more about this, thanks for reading!

Kommentare